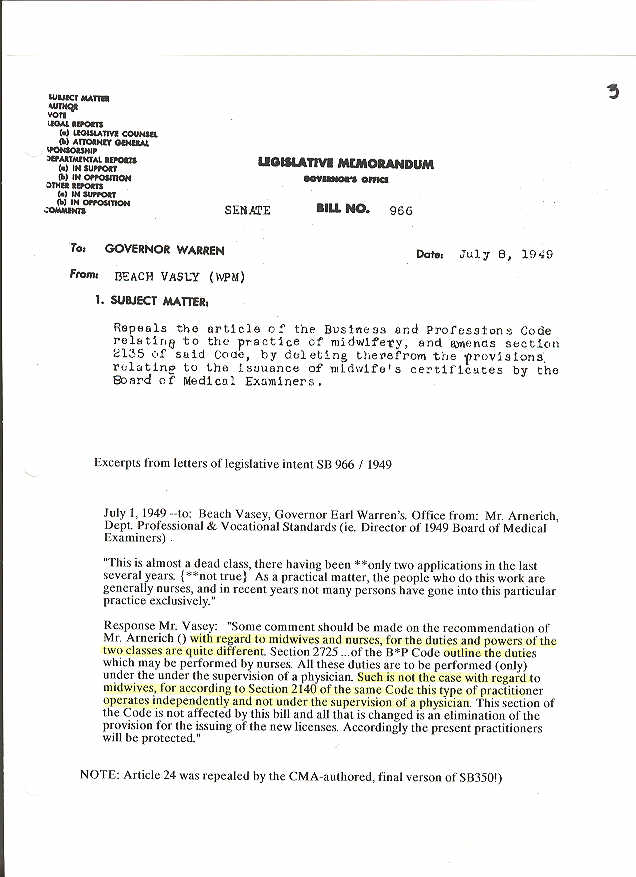

Legislative Memorandum from the Office of Governor Earl Warren, 1949 ~

Reader Reference: Pertinent quote is in the last paragraph, which is a comment addressed to Mr Arnerich, director of the Board of Medical Examiners. His letter recommending the repeal of midwifery licensing stated that midwifery was almost a "dead class" (not actually true) as no one wanted to be a midwife anymore and that as a practical matter, midwifery generally was done by nurses.

"Some comment should be made on the recommendation of Mr. Arnerich, with regard to midwives and nurses, for the duties and the powers of the two are quite different. Section 2725 ...of the B&&P Code outline the duties which may be performed by nurses. All these duties are to be performed under the supervision of a physician. Such is not the case with regard to midwives, for according to Section 2140 of the same Code, this type of practitioner operates independently and not under the supervision of a physician."

This statement identifies that midwives were originally "independent practitioners" and that when midwifery is subsumed under nursing, that quality of "practitioner" status is lost. It also acknowledges that community-based midwives have never, in the history of California, functioned under physician supervision (since the 1993 LMPA phys supervision clause also cannot and has not been implemented.

Background: This memorandum and other associated documents were obtained by ordering the "bill set" for SB 966 (1948-49 legislative session) from the archives of California legislation. Bill sets provide a copy of all letters in support or opposition of a bill before it was passed. These documents identify how and why the 1917 Midwifery Certification/Licensure program was suddenly dismantled in 1949.

The short story is that repealing the application for midwifery licensure (which blocked all further licensing) was done so at the request of the medical board without the knowledge or participation of the 46 licensed midwives practicing at that time. Of the half dozen letters supporting or neutral to the repeal of mfry licensure, not a single one was from any certified midwife, midwifery organization, any public or consumer groups.

One would have had to be a scholar of the medical practices act to realize the impact of this SB 966, which repealed the lunch-pin of the original 1917 provision -- the application. SB 966 did not say anywhere -- either in the title or text -- that the consequence of this act would be to abolish the entire classification of state-certified midwifery. Chapter 898 (1948-49 Session) merely says:

"An Act to repeal Article 9 and to amend section 2135 of Article 5, Chapter 5 of the Business and Professions Code, relating to midwives." Section 1 reads: "Article 9 of Chapter 5 of Division 2 of the B&P Code is hereby repealed."

Article 9 was the application for licensure. Then SB 966 states that the board shall issue three forms of certificates under its seal and signed by the president and secretary, designated as: (a) Physician's and surgeon's certificate, (b) Drugless practitioner's certificate, (c) Certificate to practice chiropody" (podiatry). Conspicuous by its absence is the midwifery certificate. We just got left off the list.

The passage of the original 1917 midwifery provision was equally obscure in its wording and also without the participation of those most affected by its passage -- practicing midwives. It was only a partial sentence tacked on to a 1917 amendment to the medical practices act and established criminal penalties for the use of drugs or surgical instruments by midwives. It also provided for state certification and regulation of midwives, which were defined in the law as "not authorized to practice medicine or surgery" (the same exact phase survives today in the LMPA of 1993). The 1917 version was a sort of "boys toy vs. girls toys" dichotomy. This meant that midwives weren't permitted to play with "boy toys", stated as prohibiting the use of any "artificial, forcible or mechanical means" -- drugs to stimulate labor, instruments such as forceps, podalic version and manual (non-emergency) removal of the placenta. This same phase is included in the LMPA and the same principles apply.

The 1917 provision was not a "midwifery practice act". That is, it did not "entitle" midwives to exclusive control over their own profession of midwifery but rather created mechanisms for control of midwives by the all-doctor medical board (this also survives in the current LMPA). To have given give midwives the same exclusive entitlement that physicians, nurses, chiropractors, podiatrists, etc, enjoyed, would have required doctors to train and become certified in midwifery if they wished to provide maternity care to healthy women with normal pregnancies (the classical definition of midwifery). Organized medicine successfully prevented the entitlement of midwives to the profession of midwifery again in the LMPA of 1993. You might say that while midwives are not permitted to play around with the "boy toys" of medicine, doctors are permitted full and unfettered access to the "woman's work" of midwifery.

Like the 1949 repeal of midwifery certification, the original 1917 midwife provision was also without written with the knowledge or participation of practicing midwives (women did not yet the right to vote). One newspaper reported on the passage of the "Gebhart Bill" (3/18/1917), describing it as to "make it more difficult for medical schools not sanctioned by the state board of medical examiners, the assembly passed a bill by Gebhart of Sacramento, providing technical changes in the present law." Technical changes...? Another newspaper reported on the passage of AB1375 with a headline that read: "Public Drinking Cups and Towels Opposed by Senate." (3/36/1917). The first sentence said "By a vote of 30 to 4, the senate yesterday passed Assemblyman Lee Gebhart's bill providing for the licensing and examination of midwives by the state board of medical examiners. Senator Herbert Jones championed the measure in the upper house." The specific reference to midwifery in the Gebhart bill read: "and to add a new section thereto to be numbered 24, relating to the practice of midwifery, providing the method of citing said act, and providing penalties for the violation thereof."

Some of the other "technicalities" included a requirement that midwifery training programs be "approved" by the Medical Board -- a poison pill that built the slow death of certified midwifery in at the very beginning. The Medical Board just never approved a single midwifery program in the state of California. Note that AB 1375 was specifically designed to make it more difficult for medical (and midwifery) schools not "sanctioned by the Board of Medical Examiners". The only other way to fulfill the educational requirement was to graduate from medical school (which did not accept women students) as the midwifery curriculum was the exact same 140 hours of "obstetrics" education that was required for medical doctors. Graduation from medical school was listed as one of the ways to qualify for midwifery certification.

The initial "grandmother clause" of 1917 permitted 102 practicing midwives to qualify directly for certificates in 1917-1918. Over the next three decades another 111 midwives qualified by taking the licensing exam after providing proof of graduation from a "qualified program" in another state or overseas. By 1949 a total of 216 midwives had been state certified. After the initial wave of credentialed midwives (FX status), the only way to become licensed was via "reciprocity" from formal training programs, which were mainly in Japan and Europe. The majority of state-certified midwives (about 75) graduated from one of 27 different professional midwifery schools in Japan. Medical board records show 7 Italian schools with 15 licentiates, 7 schools in the USA (St Louis, Missouri, Illinois, Wisconsin, New Orleans, Bellevue and Columbia NY), one each in England and Switzerland, 3 schools in Mexico and 3 in the USSR. But none ever in California (true to this day!)

In 1942 the entire Japanese populations, including state certified midwives, were forced to leave California and into internment camps in far distant states. Credentialing records note addresses for all midwives with Japanese surnames for places such as Heart Mountain, Montana, Poston and Rivers, Arizona (Camp 2), Relocation Branch, McGehee or Denson, Ark, and Topaz, Utah. This meant that there were almost no birth certificates identifying midwife-attended births during during WWII and immediately thereafter (the Department of Health reported only .2% in 1946). This circumstance, along with other "half-truths", was successfully used to argue that midwives were a dying breed, midwifery taken over my nurses, licensing obsolete and a useless burden to the Board of Medical Examiners. SB 966 was designed to relieve them of that burden without bringing any public attention to the issue. It was a perfect plan.

In 1949, 32 years after the original "grandmother" provision, most midwives were of retirement age and new midwives were not being licensed since there were no midwifery training schools in California. The only exception was an occasional application for certification via reciprocity. On average, 3.86 midwives applied for reciprocity between 1919 and 1948. However, that includes 4 out of 29 years when the number of applications was zero, 7 years with only one application and one year (1922) in which a grand total of 13 Japanese midwives sat for the exam. After 1930, never more than 5 midwives applied in any single year. In 1948, only one application was received -- an Italian midwife requesting reciprocity.

SB 966 was introduced only 3 years after the end of the WWII (in which Japan and Italy were our enemies) and so the idea of licensing midwives by reciprocity from these countries was not popular. The 46 practicing midwives were either elderly and/or Japanese. In any event midwives did not have any effective political organization or even a consciousness of their civil rights.

It was all too easy for the medical community to quietly pull the plug on the midwifery application and dispense with the "midwife problem" once and for all. SB 966 did just that.